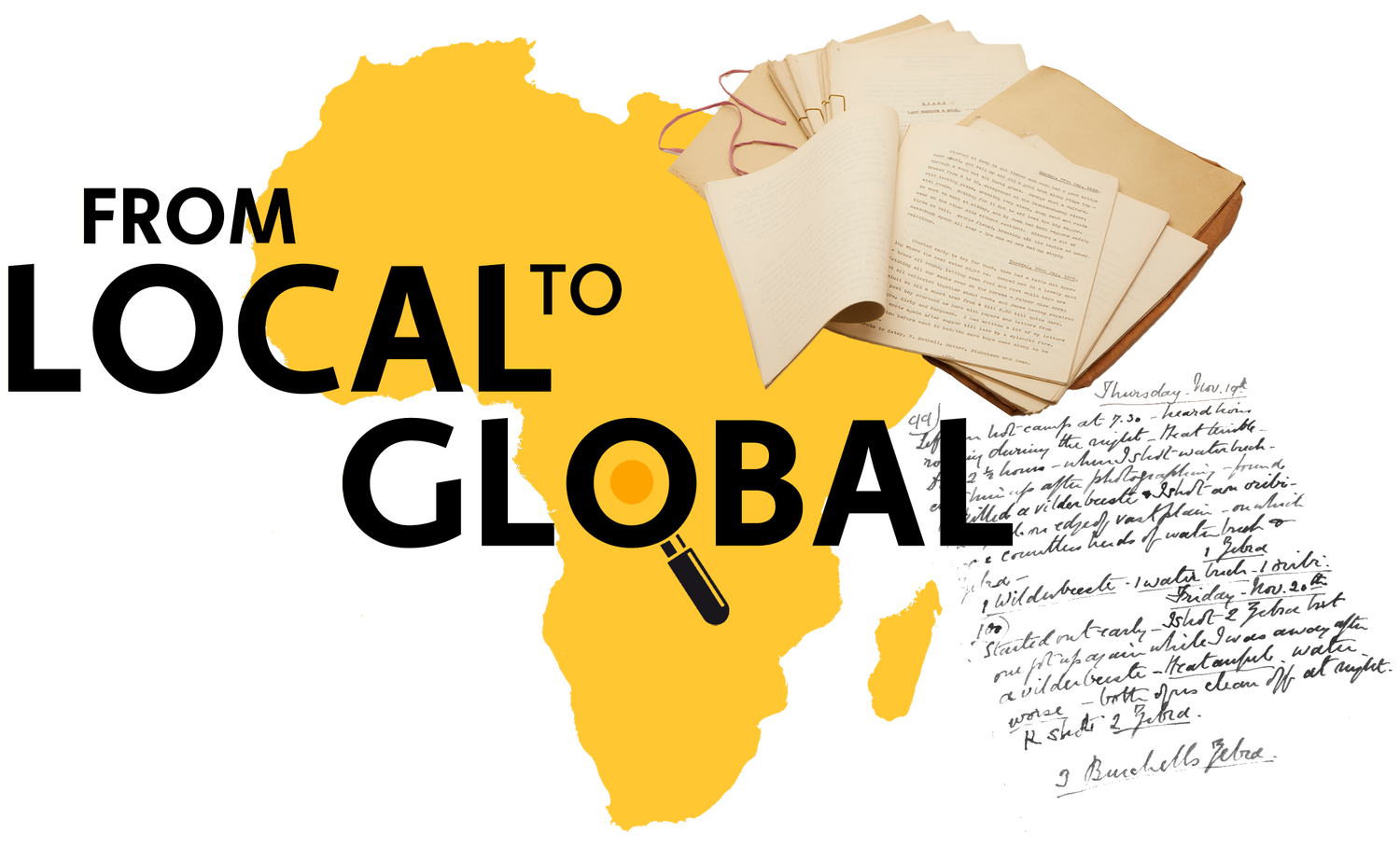

Colonel James Harrison

By Jeffrey Green

James Harrison’s Birth Certificate

When Jonathan Stables Harrison registered the birth of his son in 1857 he informed the registrar that he was a “landed proprietor” who resided at Brandsburton [sic] Hall, Beverley. His son – James Jonathan Harrison – had been born on 8 July 1857 in Park House, Selby, which was in the neighbourhood of the mother’s family. Liza Jane Harrison nee Whitehead was also part of Yorkshire’s landed gentry, her father like Harrison serving as a deputy lieutenant. Both men were magistrates.

Yorkshire Hussars Booklet

James Jonathan Harrison was the only son: he had four sisters. He went to Harrow and then to the equally exclusive Christ Church, Oxford. He joined the chic Princess of Wales’s Own Yorkshire Hussars, serving as a lieutenant. By 1895 he was a captain and by January 1902 one of the regiment’s four majors. He never saw action, and retired in 1904 with the honorary rank of lieutenant colonel.

He lived at the Hall in Brandesburton where Harrisons had owned land since 1842. The family had it rebuilt in the 1870s. Jonathan Stables Harrison died at the Hall on 13 September 1884, and his son benefited from the inheritance which included rents from over a dozen farms and a house in Harley Street, London.

James Harrison now started three decades of global travel as well joining the socially exclusive Hussars. In 1892 he had a Beverley printer issue his A Sporting Trip through India: Home by Japan and America. He had been in Bermuda, North and South America, Canada and southern Africa. In 1893 he had crossed the Rockies and had visited San Diego, Yosemite, Niagara and Washington DC. The animals and birds were mounted and displayed at the Hall.

James J. Harrison with Water Buffalo, Central Africa, 1896 © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Elephant tusks for King Menelik, Abyssinia, 24th December 1899

© Scarborough Museums and Galleries

The London taxidermist Rowland Ward Ltd’s 1892 Records of Big Game established the first benchmarks for animal trophies. Domestic items were made from animals – Wardian furniture, and other examples of the taxidermists’ skill were to be found in Brandesburton Hall. Harrison's name and some of his specimens including a sparrow lark, a painted or woolly bat, and a pygmy antelope were noted in Ward's natural history publications in 1899.

Harrison wanted to hunt a white rhino and an okapi, the latter a recently ‘discovered’ resident of the immense Congo rainforests. His 1904 visit to the Congo led him to shoot enough elephants to obtain 257 kg of ivory.

The Daily News, 6 May 1905

Sold to local merchants, ivory underwrote Harrison’s African expeditions. Friends in England admired Harrison’s photographs and suggested that he brought some of the indigenous people he encountered back to Britain. He did this in 1905, despite physical and diplomatic obstacles – one became ill and was sent back; humanitarians and newspaper publicity led to the six being hospitalised in Cairo in April 1905; the British foreign secretary’s enquiry caused Harrison to rush to London to explain (Lord Lansdowne expressed distaste for the exploitation but the Africans were not British subjects and he was powerless).

Outside Brandesburton Hall

© Scarborough Museums and Galleries

The Sphere, 6 May 1905

Tatler, 16 November 1910

The Africans reached England on 1 June 1905 and lived at the Hall when not touring. Harrison accompanied them home by early 1908. The second of two more shooting trips to the Congo led Harrison to meet up with two of the veterans in 1910.

In November 1910 Harrison married Mary Stetson Clarke of Peoria, Illinois in a high society affair in London. Newspapers reported she was a big-game hunter, and the high society weekly Tatler (16 November 1910, p 66) published their photographs and two of the Hall’s rooms– trophies on the floor, walls and in fifty glass cases in the saloon. The honeymoon was in Egypt.

After a protracted illness James Harrison died at the Hall on 12 March 1923, and was cremated. His four sisters attended the church service. His widow arranged the transfer of the trophies to the local council where, by the time of her death in 1932, they were on display in Scarborough. She died in California but her grave is in St Mary’s parish church.

Evening Telegraph, 13 March 1923

Daily Mail, 15 March 1923

Mary Stetson Harrisons Grave at St Mary's Parish Church, Brandesburton

We have included the newspapers within this article to illustrate the attitudes, perceptions and language used at that time. Some of the content will now appear outdated and offensive.

About the author

Jeffrey Green, an independent historian, has been researching the activities of African people in Britain for forty years. He has lectured, participated in television and radio programmes and met many veterans. His publications include contributions to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: such as a summary of the life of William Hoffman, who crossed Africa with Stanley and was the interpreter for the Congo pygmies. His book Black Americans in Victorian Britain was published by Pen & Sword, Barnsley, in 2018.