Big Game Hunters and Collectors

By Jeffrey Green

Harrison was not alone in bringing back specimens. During the Victorian period there were many examples of animal trophies, both in natural history museums and in private homes, as well as exhibitions and fairs. Some were inventions, such as the Feejee mermaid currently in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. These creations were designed to draw in the crowds, and featured heavily in exhibitions such as those put on by P T Barnum [1]. This one was made of monkey and fish parts, featuring reptile claws, teeth, and clay and papier mâché filler, but would have drawn the crowds just as much as the genuine specimens being sent home by the explorers of the time.

Frederick Horniman © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Other collections started off as private explorations into uncharted areas of the world, resulting in individuals amassing enormous numbers of specimens. One such collector was tea merchant Frederick Horniman. Horniman was a social reformer who built his South London museum with a view to “bring the world to Forest Hill” [2]. The museum itself opened in 1890 and contained a huge Canadian walrus which has gone on to amaze visitors ever since. The enormous creature was first exhibited at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London. Dublin’s museum, opened in 1857, has a stuffed giraffe, nicknamed Spotticus, and the London Natural History Museum used to be home to an African elephant named George, who arrived in 1907 direct from the taxidermists Rowland Ward Ltd. [3] until he was replaced by a cast of a diplodocus named ‘Dippy’. It in turn was recently replaced by a whale.

“Major P.H.G. Powell-Cotton and large Gorilla, The Powell-Cotton Museum, Birchington, Kent” - Postcard from Jeff Green

Another wealthy individual who had an enormous collection which later became a museum, was Major Percy Powell-Cotton (1866-1940). Powell-Cotton was an explorer and naturalist whose travels included an 'around the world' trip and numerous overseas collecting expeditions. Like Harrison, he too explored the Congo armed with a phonograph and several wax cylinders survive [4].

His museum at Quex House near Margate in Kent started in the 1890s and grew for decades. It includes a lion which nearly killed Powell-Cotton in 1906. Major Powell-Cotton made one hunting trip to Africa with Harrison, who records the event in his diary, stating that

Extract from Harrison’s diary, Saturday December 16th, 1899.

© Scarborough Museums and Galleries

“Saturday, December 16th, 1899.

Cotton slept out in a machan, hoping to see buffalo. I went down at 6 a.m. and going round the reeds suddenly heard the animals rushing through them. In hopes of getting a shot I did 2 hours wading nearly up to the waist in awful slime - a regular fever bed. Ghee[5] shot a fine lesser koodoo and Bill a gerenook - P.C. again went off to his machan[6].”

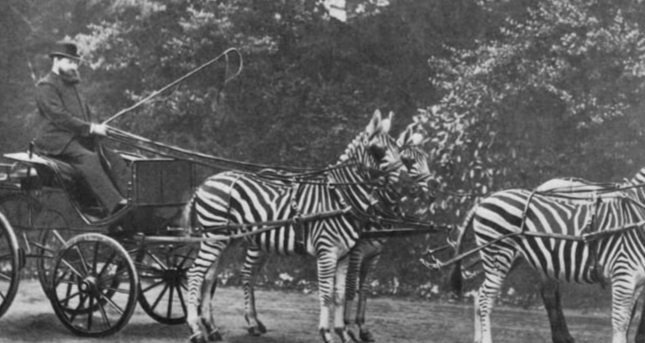

Lionel Walter Rothschild’s zebra drawn carriage

The second Lord Rothschild in Tring, part of the Rothschild banking family was another of these gentlemen collectors. Lionel Rothschild had always had an interest in insects, progressing to birds and animals as he grew older. At the age of seven he told his family that he planned on making a museum, something which he achieved by the age of ten when he had enough specimens to start one in his parents’ garden shed [7]. He eventually studied under the acclaimed zoologist Alfred Newton, at Magdalene College, Cambridge [8] and this resulted in a well established collection, which he housed in buildings on his father’s estate at Tring. When he went into the family banking business he had no time to focus on the museum, and in the end the buildings were opened to the public in 1892, given to the nation in 1937, and now form part of the Natural History Museum. He employed around 400 collectors during his lifetime and managed to accumulate specimens from more than 48 different countries [9]. His home at Tring became known as a menagerie of exotic animals, including emus, kangaroos, and zebras, which were trained to draw his carriage. Such was the intrigue around this that he was invited to drive it to the grounds of Buckingham Palace.

Okapi skins © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Central Africa’s Congo River forests were sources for many of the stuffed animals shown at an exhibition in Brussels in 1897 and then housed at what became the Royal Museum for Central Africa. The largest of its ‘unknown’ animals was the okapi, identified by European science in 1901. It is possible that the rarity of this species is what drove Harrison’s attempt to acquire one for his collection on his 1904 trip to the Congo, which was unsuccessful.

7th Edition of Rowland Ward’s Records of Big Game.

© Scarborough Museums and Galleries

British taxidermist Rowland Ward, of elephant George fame, came from a long line of taxidermists, whose work was of such renown that in 1870 the business was granted a royal warrant from Queen Victoria allowing them to announce that their work was By Appointment to Her Majesty. In 1904 Rowland Ward’s own business was granted the same status. Some of his greatest work was linked to the taxidermy he did for Percy Powell-Cotton. Rowland Ward wanted to mount Powell-Cotton’s elephant, life-size, but that would have meant considerable building work, which Powell-Cotton was not willing to do. However, Rowland Ward was so passionate about the project that he offered to carry out the actual taxidermy for free, on the proviso that Powell-Cotton organised the structural changes needed to accommodate it. The resultant piece of work can still be seen at Quex Park [10]. It was not just life size pieces that Rowland Ward was interested in though, his company was responsible for such items as “inkwells made from hoofs of horses; and letter openers with the blade made from ivory, the handle made of a fox’s paw, and the two connected with an elegant silver sleeve. Then there were liquor cabinets made from elephants’ feet; [and] stuffed birds that acted as lamp stands” [11]. He came from generations of naturalists and dealers of animal skin, and in addition to taxidermy published books listing prize specimens and new discoveries.

Rowland Ward deer stool, reproduced with kind permission from Cooling and Cooling

About the author

Jeffrey Green, an independent historian, has been researching the activities of African people in Britain for forty years. He has lectured, participated in television and radio programmes and met many veterans. His publications include contributions to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: such as a summary of the life of William Hoffman, who crossed Africa with Stanley and was the interpreter for the Congo pygmies. His book Black Americans in Victorian Britain was published by Pen & Sword, Barnsley, in 2018.

References

Ghee is the nickname Harrison gave to his friend Archibald E. Butter.

A machan is comparable to a treehouse

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/walter-rothschild-a-curious-life.html

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.